Focus on a unique form of water: superionic water

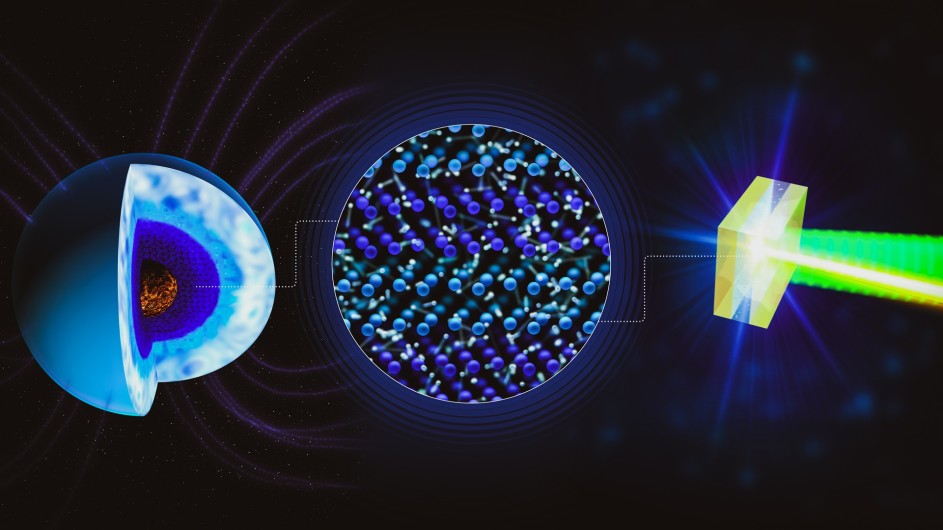

Artist's impression. Believed to be found at the core of giant ice planets, superionic water has structural defects, revealed using lasers and X-rays. Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Artist's impression. Believed to be found at the core of giant ice planets, superionic water has structural defects, revealed using lasers and X-rays. Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Solid, liquid, and gas. We think we know all about the three states of water. However, under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, this familiar element (H2O) takes on more exotic forms. In particular, water can become superionic: oxygen atoms are arranged in a fixed pattern, as in a solid, while hydrogen atoms (in the form of ions) move freely, as in a fluid.

This superionic state, predicted theoretically in the 1980s, was observed for the first time in 2018, but the details of its structure remained uncertain. However, it could play an important role at the core of giant ice planets such as Uranus or Neptune, where conditions are right for superionic water to be present in large quantities. The freedom of movement of hydrogen ions confers very good electrical conductivity, which, together with the solid matrix, could explain the magnetic field of these planets.

An elusive state to study

However, observing superionic water experimentally on Earth is difficult: pressures millions of times higher than atmospheric pressure and temperatures of several thousand degrees Kelvin must be reached. To achieve these extreme conditions, researchers at LULI and their colleagues used the facilities at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Stanford (United States) and the European XFEL in Germany, each of which has powerful lasers combined with X-ray sources, an extremely powerful microscopic probe.

In these experiments, a sample of liquid water is placed between two diamond plates. The laser beam generates a compression wave that is reflected several times between these plates, generating a series of “shocks” that compress the water. “These experiments are complex because the water must not heat up too quickly, otherwise even the matrix of oxygen atoms melts,” explains Alessandra Ravasio, CNRS research director at LULI. During this compression, an ultra-fast X-ray beam (a few tens of femtoseconds, ie 10-15 seconds) passes through the sample. When detected, these X-rays provide a diffraction pattern that contains information about the arrangement of the oxygen atoms.

Unexpected structure and defects

Atoms can be arranged in different basic patterns. For example, oxygen atoms can occupy the corners of a cube as well as the centers of the faces, in which case we refer to a face-centered cubic system. The entire structure of oxygen atoms is then formed by stacking these elementary cubes. This geometry influences the properties of superionic water.

The study reveals a much more complex structure than researchers had previously imagined. In particular, at pressures of around 150 gigapascals and temperatures of around 2500 Kelvin, two geometries are found: a face-centered cubic elementary pattern and a more compact hexagonal pattern. The stacking of these two patterns is therefore not perfect, and the misalignments lead to defects.

"When we analyzed the initial diffraction results, an unknown phase immediately caught our attention, and we nicknamed it the ‘mystery phase’. It was only after extensive analysis that we were able to determine that this unusual signature was actually caused by defects, thus solving the mystery," explains Léon Andriambariarijaona, a postdoctoral researcher at LULI who led the analysis of the diffraction results. Numerical models are consistent with these observations.

This work highlights that water, despite its simplicity, continues to surprise us with its astonishing properties. The results also provide useful constraints for improving models of the interiors of giant ice planets and their evolution.

Scientific article reference:

Andriambariarijaona, L., Stevenson, M.G., Bethkenhagen, M. et al. Observation of a mixed close-packed structure in superionic water. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67063-2

*LULI: a joint research unit CEA, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, École polytechnique, Institut Polytechnique de Paris, 91120 Palaiseau, France

**The collaboration was funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) and the German Research Foundation (DFG). More than 60 scientists from European and American institutions contributed to the experiments and analyses, including LULI, the University of Rostock, European XFEL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, CEA, Queen's University Belfast, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), and Sorbonne University.

Support l'X

Support l'X