Synthesizing exotic nanomaterials at high temperatures

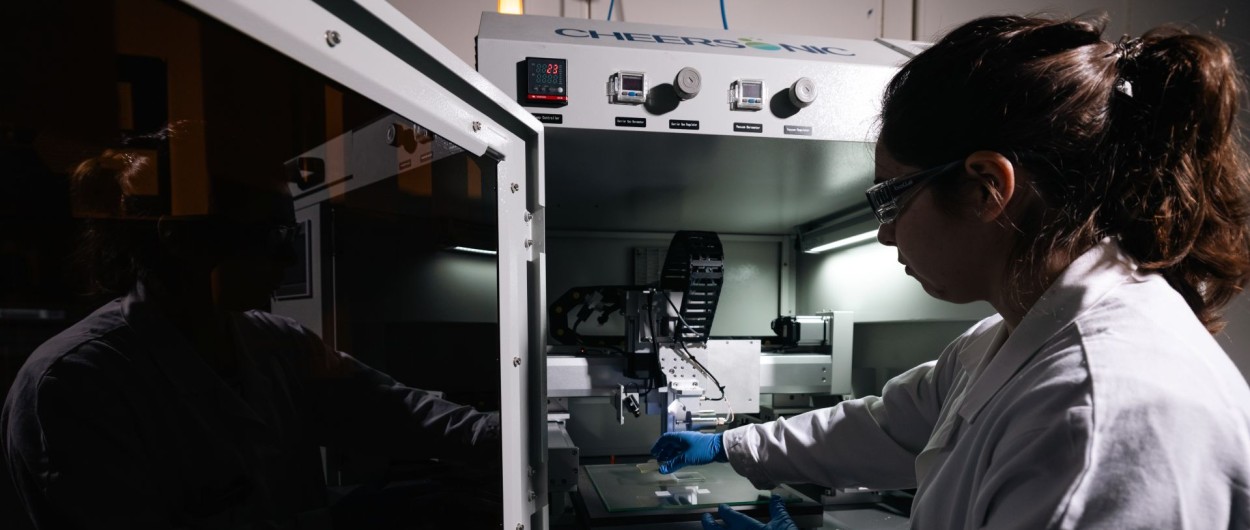

Amandine Séné, postdoctoral researcher at PMC, prepares thin layers of chemical precursors for the synthesis of nanomaterials.

Amandine Séné, postdoctoral researcher at PMC, prepares thin layers of chemical precursors for the synthesis of nanomaterials.

A glass flask, various substances mixed in water and heated with a Bunsen burner: this is the image we often have of chemical synthesis. And this image is not necessarily wrong: many materials can be formed using water as a solvent. “But there is a limit: the boiling temperature of water. Some materials, such as diamond, require temperatures well above 100°C to crystallize. It's true that other organic solvents have higher boiling points, but these remain limited,” notes Simon Delacroix. This chemist, assistant professor in the Chemistry Department at Ecole Polytechnique and Institut Polytechnique de Paris since September 2023, is developing new high-temperature synthesis methods with his team.

Molten salts

One of the alternatives explored by Simon Delacroix during his thesis at Collège de France and Sorbonne Université was the use of “molten salts”. Similar to table salt, these salts can be heated very strongly before melting. “The result is a high-temperature-stable liquid - 900°C or more - in which the same kind of chemistry can be performed as in water. He has applied this method to create nanoparticles in molten salts.

The synthesis of nanomaterials raises an additional challenge: when the chemical reactants are heated very strongly, the particles formed grow very quickly, reaching the micrometric scale, which is 1,000 times larger than the nanometric scale. While the use of molten salts provides solutions (the liquid medium reduces the crystallization temperature and minimizes the time spent at high temperature), another technique can overcome this problem: laser synthesis. “Unlike an oven, a laser can heat up very quickly at high temperatures”, explains Simon Delacroix, who also specialized in this field during a post-doctoral training at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam (Germany).

An original method for nanomaterials

One of the projects he has launched at the Laboratory of Condensed Matter for Physics (PMC*) combines these two methods. In particular, it involves synthesizing boron carbide nanoparticles. “This is a material with remarkable thermoelectric properties and exceptional hardness, thanks in particular to the bonds between carbon and boron atoms, similar to the carbon-carbon bonds in diamond. These two properties could be further enhanced by using the smallest possible particles. A great deal of energy is required to form these bonds and organize the crystalline structure, hence the need for high temperatures. To limit growth, the idea is to proceed in several stages. Precursors and salt are placed in a crucible and heated to 900°C in a furnace. After cooling and washing to dissolve the salt, a solution containing sodium borocarbides (NaB5C) is obtained. This solution is deposited in a thin layer on a substrate, then irradiated with a laser beam. Under the beam, the temperature rises to 1500°C, breaking the bond with the sodium to give nanostructured boron carbide ready for use.

This method has the advantage of being versatile, since depending on where the laser beam passes, it is possible to form an entire nanometric layer of the material, or just a few nanoparticles at selected spots. “This original method is very promising, as it is very complex to create nanometric layers or crystals of boron carbide using current standard methods,” explains Simon Delacroix. Boron carbide is not the only material in the researcher's sights, as he uses these atypical synthesis methods, in particular laser synthesis, to make luminescent oxides and colored glasses.

*PMC: a joint research unit CNRS, École Polytechnique, Institut Polytechnique de Paris, 91120 Palaiseau, France

Support l'X

Support l'X